On October 26, delegations from the Fort Peck Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes, Oglala Sioux Tribe, Rosebud Sioux Tribe, Yankton Sioux Tribe, and Northern Arapaho Tribe traveled to Washington, D.C., to see the Treaty of Fort Laramie installed at the National Museum of the American Indian. Signed in 1868, the treaty was broken less than ten years later when the United States seized the sacred Black Hills. In 1980, the Supreme Court ruled that the United States had acted in bad faith, but the issue remains unresolved.

October 30, 2018

“It is my wish that the United States would honor this treaty.” —Chief John Spotted Tail (Sicangu Lakota, citizen of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe), great-great-grandson of Spotted Tail, one of the treaty’s original signers

Between April 29 and November 6, 1868, tribal leaders from the northern plains came forward to sign a treaty with representatives of the United States government setting aside lands west of the Missouri River for the Sioux and Arapaho tribes. In this written agreement, negotiated at Fort Laramie in what is now Wyoming, the United States guaranteed exclusive tribal occupation of extensive reservation lands, including the Black Hills, sacred to many Native peoples. Within nine years of the treaty’s ratification, Congress seized the Black Hills. By breaking the treaty, the United States initiated a legal battle for ownership of the Black Hills that continues to this day.

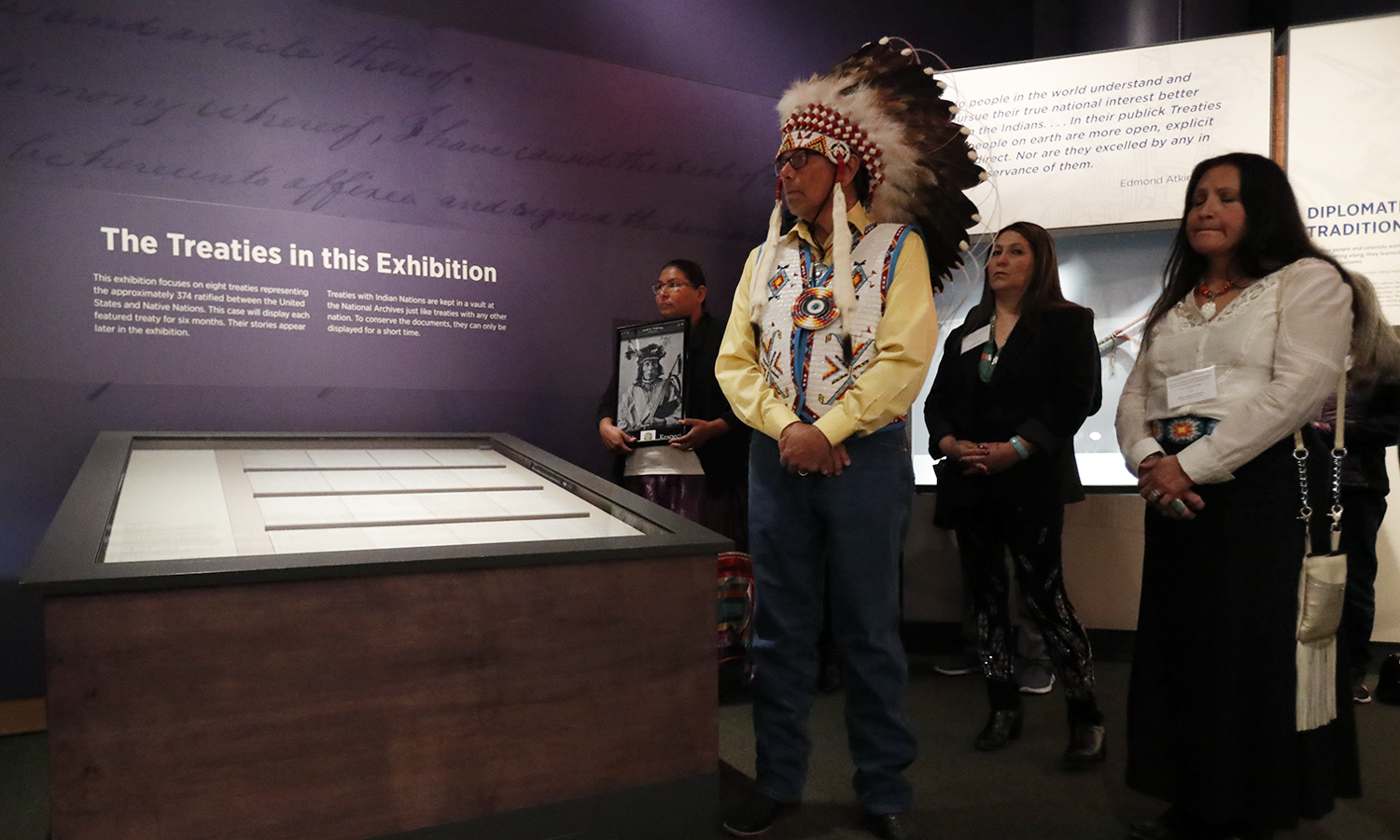

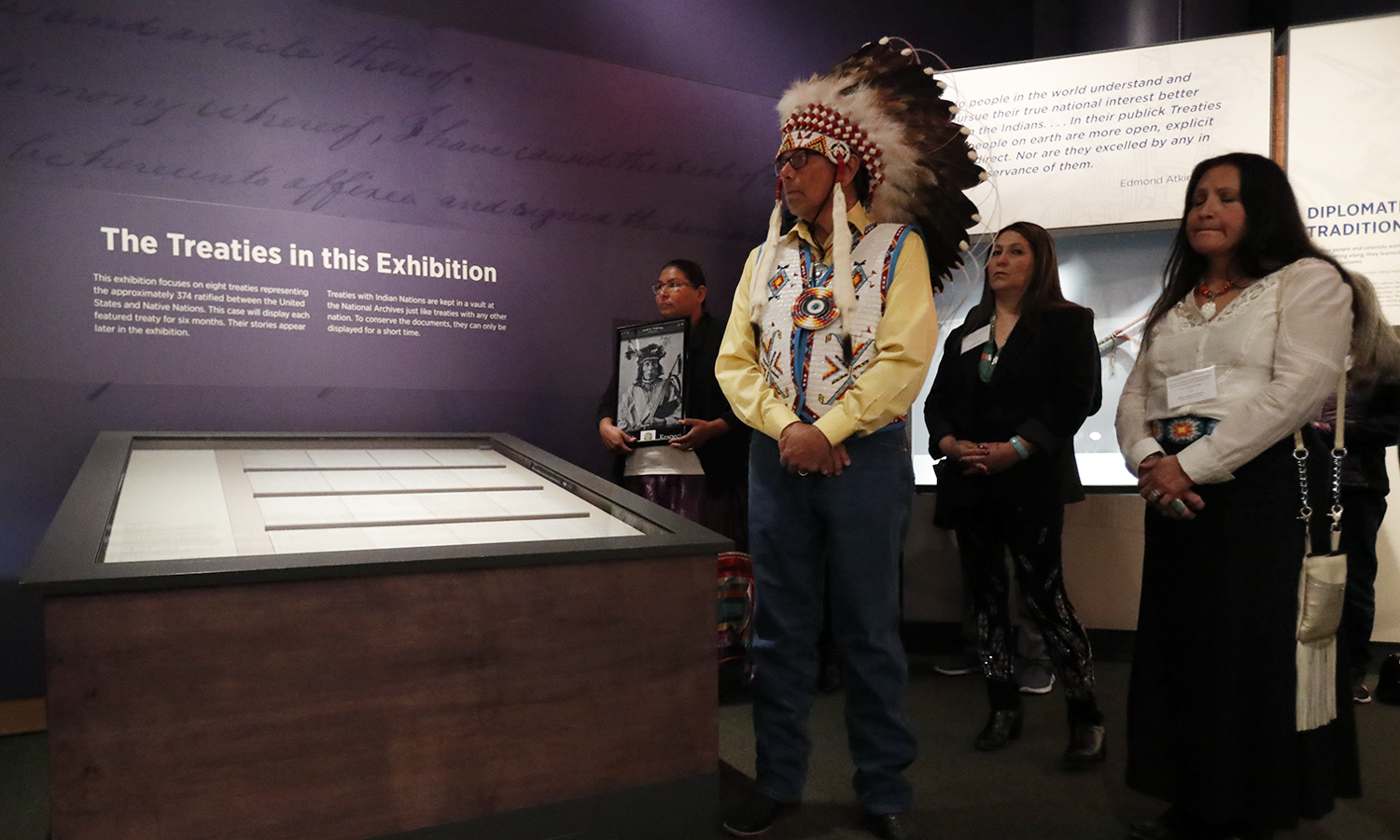

On October 26, 2018, five tribal delegations—representatives from the Fort Peck Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes, the Oglala Sioux Tribe, the Rosebud Sioux Tribe, the Yankton Sioux Tribe, and the Northern Arapaho Tribe—traveled to the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C., to see the treaty their ancestors signed and take part in its installation in the exhibition Nation to Nation: Treaties Between the United States and American Indian Nations. Kevin Gover (Pawnee), director of the museum, began by welcoming the delegations to the museum. Michael Hussey, deputy director of exhibits for the National Archives, also spoke. The National Archives holds 377 ratified American Indian treaties and is in the process of digitizing all of them so that they can be available online for Native and non-Native Americans to see.

Leaders of the five tribes then followed traditional protocols of the northern plains to honor the unveiling of the treaty. The honors included a pipe ceremony, prayers, oratory, and songs. Afterward representatives of the tribes expressed their feelings concerning the treaty. Devin Oldman, historic preservation officer for the Northern Arapaho, reminded the audience, “A lot of tribes forgot the debt that the United States promised to Indian people.”

“One does not sell the earth upon which the people walk.” —Crazy Horse (Oglala and Mnicoujou Lakota)

The Treaty of Fort Laramie was born of war on the northern plains. Led by Chief Red Cloud, the Sioux and their Cheyenne and Arapaho allies defeated U.S. Army detachments and halted wagon trains moving across the Dakotas into the Wyoming and Montana territories. With its soldiers subdued, the United States dispatched peace commissioners to reach a settlement. The United States agreed to guarantee exclusive tribal occupation of reservation lands encompassing the western half of present-day South Dakota and sections of what are now North Dakota and Nebraska; recognize tribal hunting rights on adjoining unceded territories and bar settlers from them; and forbid future cessions of tribal land unless they were approved by 75 percent of the Native men affected by them. The treaty also required families to send their children between the ages of six and 16 to school on tribal land—for the first 20 years, the government was to provide a classroom and teacher for every 30 children—and promised incentives for Native people who began farming for a living.

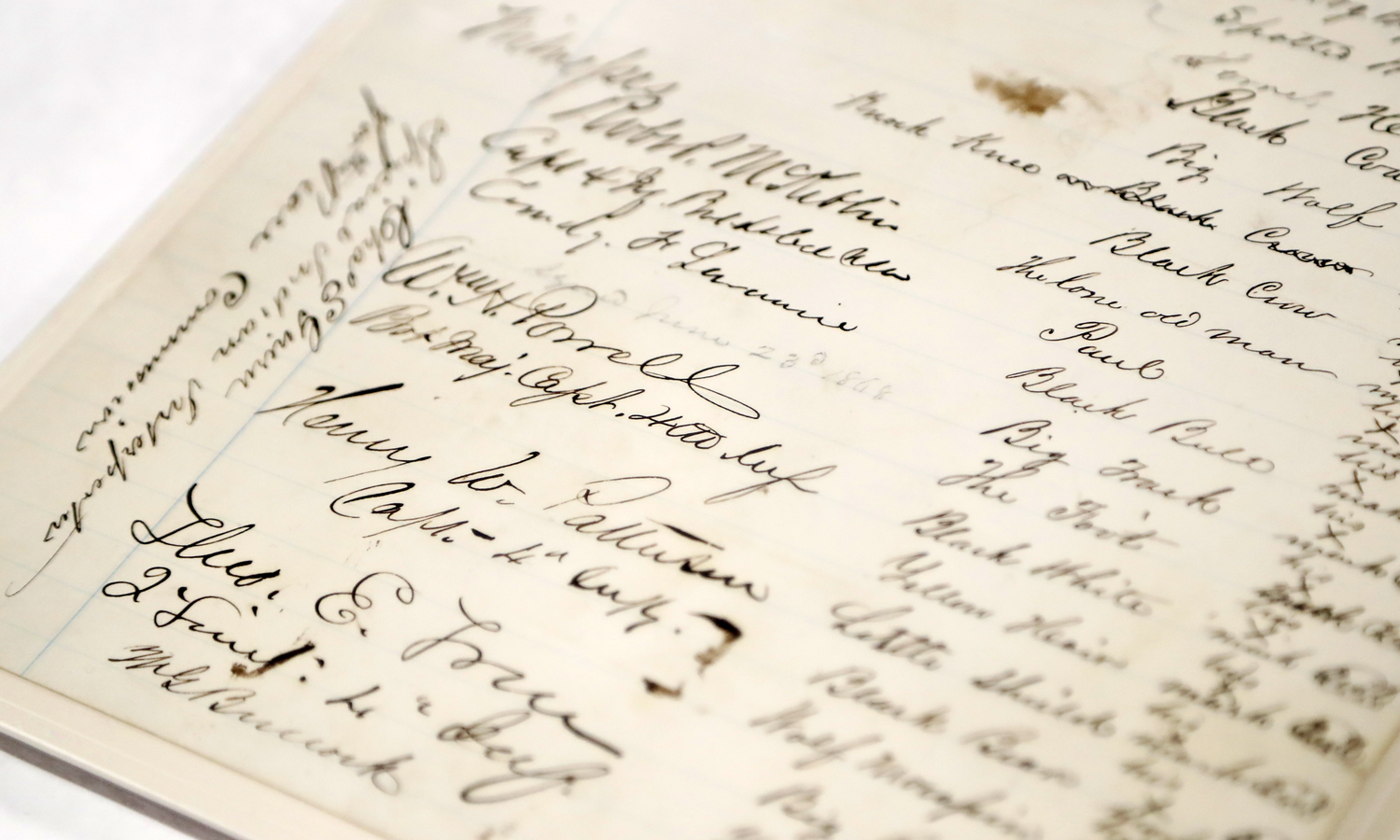

The tribal nations that took part in the negotiations include the Santee and Yanktonai (Dakota); Hunkpapa, Itazipco, Mnicoujou, Oglala, Oohenumpa, Sicanju, Siha Sapa, Sisitonwan, and Wahpetonwan (Lakota); Ikhanktown/a (Nakota); and Hiinono’ei (Arapaho). Red Cloud and five other Native representatives declined to sign the treaty until the United States made good on a provision requiring the army to abandon military posts on Sioux lands within 90 days of peace. In the end, 156 Sioux and 25 Arapaho men signed, alongside seven U.S. commissioners and more than 30 witnesses and interpreters.

In 1874, gold was discovered in the Black Hills. This discovery spurred thousands of gold seekers to invade the Sioux lands, despite the United States' solemn agreement. Less than nine years after the Treaty of Fort Laramie was negotiated, Congress seized the Black Hills without the tribes' consent. The Congressional Act of February 28, 1877, offered compensation. But the Sioux lands guaranteed to them by the United States were never for sale.

In 1980, in the United States v. the Sioux Nation of Indians, the Supreme Court ruled that Congress had acted in bad faith. The courts set fair compensation for the Black Hills at $102 million. It is estimated that the settlement’s value has appreciated to $1.3 billion today. The Sioux, however, will not accept this payment. They contend that they do not want the money. What they want is their sacred Black Hills back. In addition, Sioux leaders argue, $1.3 billion, based on a valuation of the land when it was seized, represents only a fraction of the gold, timber, and other natural resources that have been extracted from it.

The display of the Treaty of Laramie in Nation to Nation commemorates the treaty’s 150th anniversary. The treaty will be on view on the fourth floor of the museum through March 2019. The tenth in a series of original treaties on loan from the National Archives to the exhibition, the Treaty of Fort Laramie is the first that will not be shown in its entirety. The case can only accommodate 16 pages of the 36-page treaty. The exhibition features the pages where tribal leaders’ and U.S. repesentatives' made their marks. The entire treaty can be seen online at the National Archives.

The National Museum of the American Indian is committed to advancing knowledge and understanding of the Native cultures of the Western Hemisphere—past, present, and future—through partnership with Native people and others. The museum works to support the continuance of culture, traditional values, and transitions in contemporary Native life. To learn more about programs and events at the museum in Washington, D.C., and New York City, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, or visit AmericanIndian.si.edu.

Dennis W. Zotigh (Kiowa/Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo/Isante Dakota Indian) is a member of the Kiowa Gourd Clan and San Juan Pueblo Winter Clan and a descendant of Sitting Bear and No Retreat, both principal war chiefs of the Kiowas. Dennis works as a writer and cultural specialist at the Smithsonian's National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C.